Historically, inside linebackers are the most amorphous position in football.

Picking the best of the best is sheer folly.

These men began as the sole middle linebackers in various fronts, most popularly the 4-3. This MLB was a big, brutal interior enforcer against the early, run-oriented offenses.

But as those offenses—and the resulting needs of defenses—evolved to embrace more passing, that middle linebacker became one of two inside insider linebackers, most often in a 3-4 alignment.

And now? Pffft!

Today’s inside linebackers are a shadow of their positional ancestors as they are often tasked with covering fast running backs, tight ends, or receivers. So, they are the first defenders replaced in what once was called “situation substitution.”

The fact is that, with the league-wide average of 96 percent of defenses having one or no inside linebacker, the position has been removed from so-called base alignments.

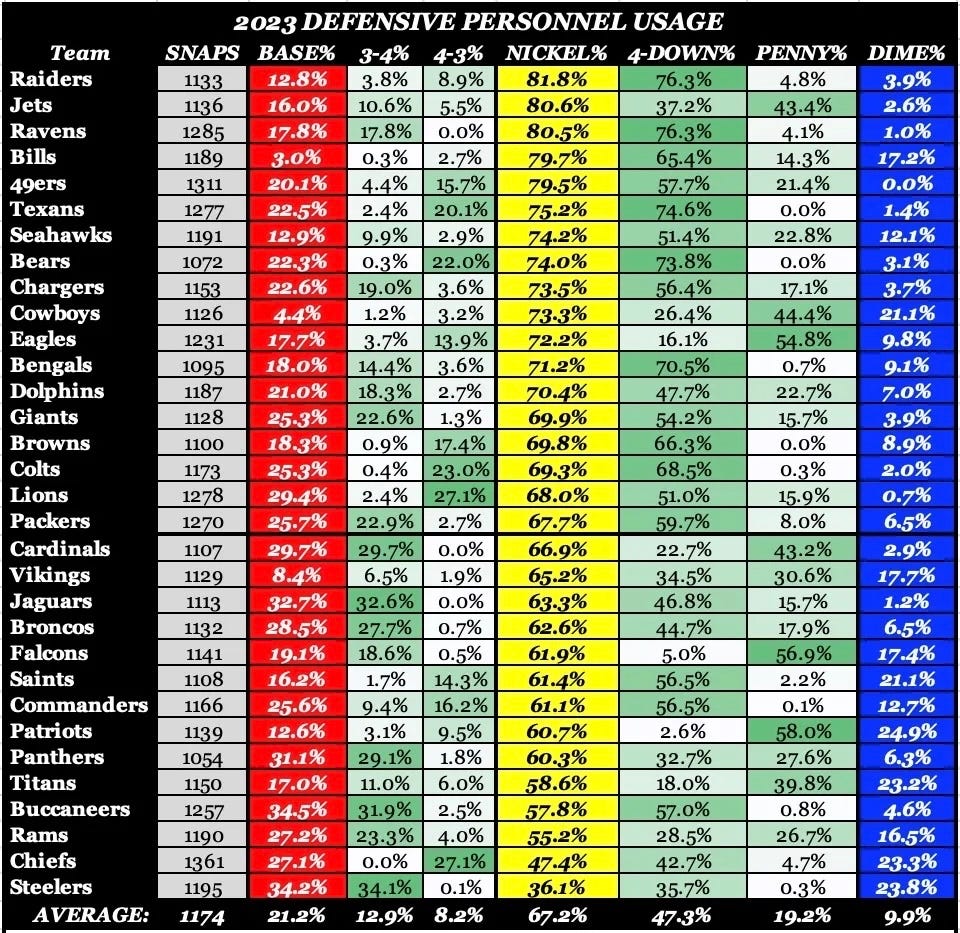

In 2023, NFL teams used the nickel defense, with one ILB and five DBs, more than 67 percent of the time. Teams used the dime (six DBs, no ILBS) and the penny (seven DBs, no ILBs) 29 percent of the time (see chart below). That adds up to more than 96 percent.

Hence, pffft!

But here we are, stubbornly including ILBs in a series on football positions.

Our Gordon Justyce scouted the best ILBs in the 2025 Draft. Jeremy Bissett tried to pick out 2024 draftees who could make an impact at ILB. We also dove into our college and high school database to see the ILBs on the horizon, up to about the 2030 draft.

Charting the demise of inside linebackers:

The Pro Football Hall of Fame lists 18 middle or inside linebackers as the best of the best at this disappearing position.

And, since 2018, three MLB/ILB stars have been inducted: Brian Urlacher (2018), possibly the last of the Monsters of the Midway; Zach Thomas, diminutive disruptor who got into the minds of quarterbacks; and Patrick Willis, possibly the most physically gifted inside linebacker in pro football history.

Here are the current MLB/ILB Hall of Famers.

Chuck Bednarik (MLB) *,PHI, 1949–1962, Class of 1967 Nick Buoniconti (MLB), BOS, MIA, 1962–74, 1976, Class of 2001 Dick Butkus (MLB), CHI, 1965–73, Class of 1979 Harry Carson (MLB), NYG, 1976–88, Class of 2006 George Connor (also DT, OT), CHI, 1948–55, Class of 1975 Bill George, CHI, LAR, 1962–66, Class of 1974 Sam Huff (MLB, NYG, WSH, 1956–67, 1969, Class of 1982 Jack Lambert (MLB), PIT, 1974–84, Class of 1990 Willie Lanier (MLB), KC, 1967–77, Class of 1986 Ray Lewis (MLB) BAL, 1996–2012, Class of 2018 Ray Nitschke (MLB), GB, 1958–72, Class of 1978 Les Richter, RAMs 1954–62, Class of 2011 Joe Schmidt (MLB), DET, 1953–65, Class of 1973 Junior Seau (MLB), SD, MIA, NE, 1990–2009 Class of 2015 Mike Singletary (MLB), CH, 1981–92, Class of 1998 Zach Thomas (MLB),MIA, DAL, 1996-2008,Class of 2023 Brian Urlacher (MLB), CHI, 2000–12, Class of 2018 Patrick Willis (ILB), SFO, 2006–14, Class of 202

Who would you pick as best?

In his day (1965–73), Dick Butkus of the Chicago Bears was so brutal that opponents admitted he scared them before the ball was snapped by grunting various sounds or words.

—Dick was an animal. I called him a maniac. A stone maniac. He was a well-conditioned animal, and every time he hit you, he tried to put you in the cemetery, not the hospital. — Deacon Jones, Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive end

Quarterback Dan Pastorini and others discuss confronting Dick Butkus

In the same era, the New York Giants had Sam Huff, whose TV feature The Violent World of Sam Huff was imprinted into the minds of the times. Green Bay's Ray Nitschke had a huge following in the same era. Most fans who revered them didn't care about the nuanced play of anybody who followed. Nuance wasn't part of the football lexicon, especially not at middle linebacker.

From 1996 to 2012, Baltimore Ravens ILB Ray Lewis — with all his pregame pomp and ceremony — was pegged by fans of that era as the best ever. A social media survey even asked who the best inside linebacker in pro history was — Butkus or Lewis?

That is one myopic example of social media's limitations or outright stupidity: Which is better, pomegranates or peaches?

Lewis was outstanding when he played, but — be it better, worse, or whatever — he did not play the game the same way as Butkus, Huff or Nitschke. Lewis used his athleticism to be what players call a “runaround” linebacker, meaning he would more often run around an obstacle than take it on. Linebackers from the early era probably would not fit into the modern game, and very few current ILBs could hold up as an old MLB, regardless of how much they insist otherwise.

There is a measure of truth to the era differences in many football positions. With inside/middle linebackers, it is just more pronounced. And even when discussing some of the best, we each have our own perspective.

Mike Singletary (Chicago 1981–92) is an interesting subject. He captured fan attention with his wide-open eyes (wonder who would win a stare-down between Roger Craig and Singletary). He was the middle linebacker for the historic Bear defense of the time. Yet it is difficult to compare him to any other linebacker.

Singletary was an excellent player, but the nature of the defense prevented offensive players from getting to him. Singletary may have set an NFL record for the cleanest uniform in a career, but he did take advantage of the situation quite well.

xxxx

I have a couple of personal favorites. Neither is in the Hall of Fame, but both had historic Super Bowl moments and are examples of the position's evolution.

Jack “Hacksaw” Reynolds and Matt Millen deserve a place of honor in the history of middle/inside linebackers.

Reynolds was a first-round pick by the Los Angeles Rams (No. 22 overall) in 1970. After 11 seasons, two Pro Bowls, and a Super Bowl loss, he gained rare free-agent status and was signed by the San Francisco 49ers in 1981.

He remains the most forgotten key element in the 49ers’ surge to a Super Bowl XVI championship.

Everybody remembers the coming-out party for 1979 draftee Joe Montana and 1981 first-round pick Ronnie Lott's leadership of a rookie-laden defensive backfield. But Lott says Reynolds and his freakish, obsessive preparation for games showed the way.

Reynolds didn’t much like the media when the 49ers signed him. I called the one journalist from SoCal to whom Hacksaw talked — Ken Gurnick. Ken said Reynolds would test me, so be ready. He did and I was.

“Sure, I’ll talk, but I don’t want to waste time, so come with me to study films,” Reynolds said,

So, I did, at 5 a.m., in the team’s Redwood City facility for five days. He would manually sharpen a box of No. 2 graphite pencils, get a new, yellow legal pad, and settle in to take notes off game films for at least a few hours.

“Didn’t think you would hang,” Hacksaw said. “You are damn near as crazy as me.”

Guilty.

Hacksaw, only about 6-1 (at most), 225, had been a 4-3 middle linebacker, and a damned good one, for the Rams. The 49ers wanted him as an inside linebacker and on the weak side. He bitched until they moved him to the strong side, just in time for the playoff run and Super Bowl. But long before that, Lott declared that Reynolds was the most valuable player on that star-laden team.

“Hacksaw taught us how to prepare, how to be professionals,” Lott said. “I went to study film with him one morning, and he kicked me out when I asked for a pencil. He told me to come prepared.”

The retread linebacker leader helped the 49ers to a Super Bowl championship in one year, where the Rams had never gone. This 11-year veteran's impact on a young defense was more profound than mere statistics, although he did lead the team in tackles. Many of his own teammates believe he was the binding factor that made the celebrated New Name Defense so potent.

Coach Bill Walsh credited Reynolds as being the most telling personnel move he ever made, stating "Jack gave us leadership and maturity and toughness and set an example for everybody ... As strange a guy as he was, he really put us on the map. I think that single addition was the key to our success."

"He showed the way, both before and during games, all year," said fellow linebacker Craig Puki. "I think even the coaches learned from him. Heck, they eventually used defenses the way he talked about when he first got here. And in the Super Bowl, well, he would have got my vote as Most Valuable Player. I respect Joe and what he did (quarterback Joe Montana, who won the Super Bowl MVP award). But I'll bet a lot of players might have picked Hacksaw as the MVP in the Super Bowl."

It was in Super Bowl XVI that it became evident Hacksaw was succumbing to the game's evolution. His participation was limited almost exclusively to first-down plays. Despite his reduced use, Reynolds led the 49ers with eight tackles. He was in on three of the four stops on a historic goal-line stand in the third quarter.

But his constant absence in the game became so accepted that few noticed after the goal-line stand that he peed on the Astroturf while on the sideline.

“Hey, I had to go,” he explained.

**********

I met Millen in 1980, the first day he arrived at Raiders headquarters, decked out in overalls with a toothbrush in his pocket. That’s how I remember it, and nothing since then has given me a reason to second-guess.

“Don’t remember, seems right,” Millen once said.

I watched as the 270-pound defensive tackle from Penn State was converted to an inside linebacker and became an immediate team leader. That Raiders team famously became the first wild-card entry to win a Super Bowl (XV). After the 1983 season, they won Super Bowl XVIII, 38-9, over a Washington team that set the league record for scoring and was a huge favorite.

It’s a game remembered for running back Marcus Allen’s reverse-field touchdown and 191 yards rushing and quarterback Jim Plunkett’s second Super Bowl win in a personal comeback from football hell.

But, against a record-setting offense, the Raiders’ defense was stifling. That started with 245-pound nose tackle Reggie Kinlaw (“He was in the middle of every play,” said Washington quarterback Joe Theismann). He was NOT one of the five Hall of Famers on that Raiders team, but three were on defense (Howie Long, Ted Hendricks, and Mike Haynes). Cornerback Lester Hayes also definitely belongs in the HOF.

Millen’s contribution to that game was, ah, subtle.

With 12 seconds left in the first half, Millen called for a blitz. But defensive coordinator Charlie Sumner recalled being burned by Washington in a similar situation during the regular season on a screenplay.

He sent in linebacker Jack Squirek with instructions to watch running back Joe Washington on a screen pass—and, oh yes, send Millen to the sidelines. So Millen was screaming at Sumner on the sideline as Squirek intercepted the ball and ran it in for a touchdown, giving the Raiders a 21-7 halftime lead.

“I guess Charlie knows what he's doing, huh?" Millen said after the game.

Indeed. But it once again demonstrated that the game was finding alternatives for conventional inside linebackers to cope with the league’s increasing penchant for passing the ball.

Millen went on to play in Super Bowls for two other teams—San Francisco and Washington—and win four Super Bowl rings. However, his name has not surpassed the annual preliminary list of nominations for the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

After participating in the launch of FOX Sports in 1994, I worked with Matt and watched him become one of the very best broadcasters in the game. He was touted as the heir apparent to John Madden’s throne.

But the ever-competitive inside linebacker couldn’t leave well enough alone. When asked to be president/CEO of the Detroit Lions, Millen was the first to say, “I don’t have the credentials for this.”

Alas, he apparently was right. After seven tortured years with the Lions, Millen returned to broadcasting, where producers didn’t have the insight or guts to give him a gig worthy of his ability to entertain and inform. And we, the viewers, are being short-changed.