How to watch Indy Combine with Al, Gil

Behind-the-scenes look at evolution of the popular 40-yard dash

“Excellent player evaluation for decades,” Hall of Fame general manager Ron Wolf, a long-time subscriber

— “NFL Draft Scout is for REAL football lovers—thorough, unbiased facts,” Super Bowl Champion Coach Jon Gruden.

— “We were an early subscriber. Broad, thorough, thoughtful information,” Philadelphia Super Bowl Champion owner Jeffrey Lurie.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

See early player ratings by NFL Draft Scout/Hall of Football

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

As we prepare for the 38th Indianapolis Combine media extravaganza this week, know two things: Al Davis is watching, and there should be a trophy to commemorate his zeal for the most popular event.

It would be the Al Trophy. We will get back to that.

Yes, we are aware that Davis passed away in 2011. But Al insisted, “Raiders never die,” and he would not purposely miss a Combine, his second favorite event behind only a Super Bowl win. So he is watching.

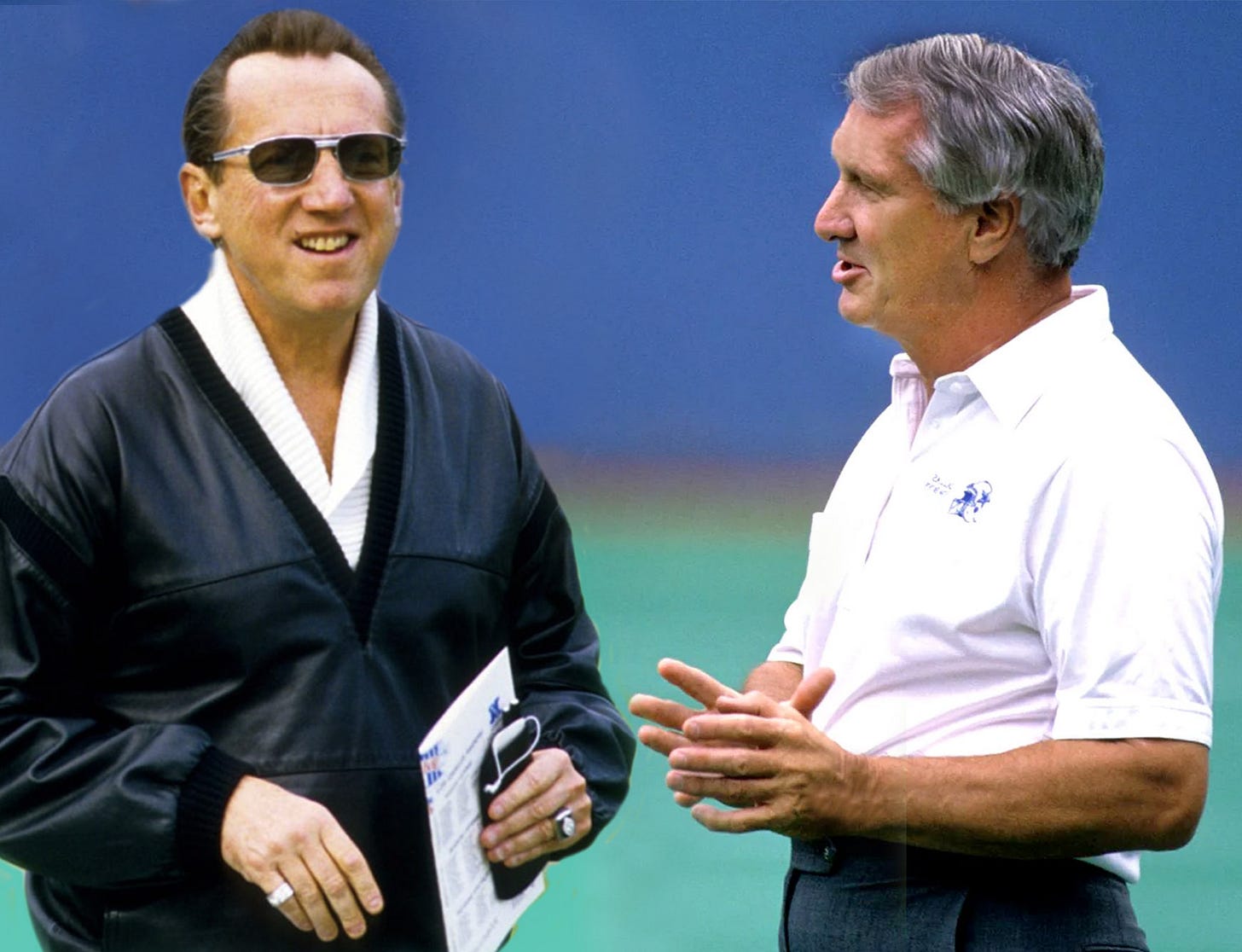

If you ever tuned in to coverage of the event between 2004 and 2011, you saw Al watching workouts from the stands alongside Gil Brandt, the Godfather of the Combine. Yes, Gil left us in 2023, but in our mind’s eye, we still see the two longtime friends watching it together, just as they did for decades. Cameras caught them sitting together in the stands, often with Bill Parcells.

Out of respect, the Combine should reserve those seats every year or put plaques with their names on them.

Davis was so enamored of the Combine that in 1987, after several regional combines merged into one at Indianapolis, he had a dream — a grand vision for what was then a lightly regarded event.

“They should televise it, get sponsorship money,” he told me after that first Indy Combine. “It’s a great event that showcases the best pro players of the future. People would love it. You like the draft and the Combine — wouldn’t you love that?”

He had me there. I did, and I do.

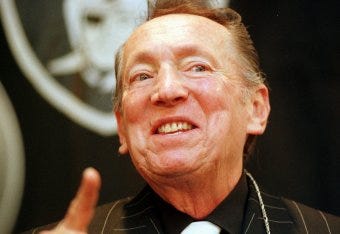

“Al also said they could sell seats for fans to watch live,” recalled Hall of Fame general manager Ron Wolf, who was with the Raiders then. “Al’s mantra for scouting players was ‘height, weight, speed,’ and the Combine provided all of that. He did love the Combine.”

However, the initial response from the league to Al’s big vision was not encouraging.

“Who would want to watch a combine?” one league official told me at the time. “It’s like watching paint dry. Really. Who would watch it?”

Who indeed.

Coverage of the 2024 NFL Scouting Combine on NFL Network reached a total unduplicated audience of over five million viewers across the four-day event.

Behind headlines, such as the “NFL Scouting Combine, draws record ratings,” stories specified that viewers, particularly those who tuned in on Saturday, were not disappointed, as they saw Combine history. The 40-yard dash, which is generally the Combine’s glamor event, especially for skill positions, featured Texas wide receiver Xavier Worthy running a Combine record 4.21 seconds.

A time of 4.21 seconds! Faster than a blink.

Can’t you just see Al giving his right-fist salute? As the story goes, the Kansas City Chiefs were able to draft Worthy only because Al couldn’t run the Raiders’ draft.

But there was a long road between Al’s dream in 1987 and that great broadcast moment last year.

After NFL Network launched on November 4, 2003, six one-hour shows recapping the day's events aired in February 2004, programming increased each year. In 2010, NFL Network began airing over 30 hours of Combine coverage, which received 5.24 million viewers.

So, that growing audience is the answer to “Who would watch it?”

Let’s take a look at the dates and times of this week’s Combine process, then get back to the Al Trophy.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

Combine Week: A player’s perspective

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

Combine Week: Attending fan’s perspective.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

Combine Week: When to watch it on NFL Network

Thursday, February 27: 3 p.m. ET for defensive linemen and linebackers

Friday, February 28: 3 p.m. ET for defensive backs and tight ends

Saturday, March 1: 1 p.m. ET for quarterbacks, wide receivers, and running backs

Sunday, March 2: 1 p.m. ET for offensive linemen

The Combine is also available to stream on NFL+ and fuboTV.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

COMBINE BACKGROUND

In 1981, the scouting groups BLESTO and National Football Scouting gathered players in Indianapolis for medical testing; no team interviews or on-field activities were conducted.

The National Invitational Camp, the official name for the NFL Scouting Combine, began in 1982. Only some teams participated, and the first National Invitational Camp was held in Tampa, Florida, with 163 players participating.

During the first three years (1982–84), two additional camps were held at different times to collect similar information for teams that did not belong to National Football Scouting. In 1985, all 28 NFL teams decided they would participate in future National Invitational Camps to share costs for the medical examinations of draft-eligible players.

After brief stints in New Orleans (1984 and 1986) and Arizona (1985), the NFL Scouting Combine moved to Indianapolis where it has been held since 1987. This is the 38th Combine in Indianapolis. The first 22 were held at the RCA Dome (called the Hoosier Dome for the eight events from 1987–94 before the building was renamed the RCA Dome). The 2025 Combine will be the 16th held in Lucas Oil Stadium.

Those of us geeky enough were actually able to identify a change in 40-yard dash times after the stadium change. That was brought into line when Lucus Oil changed to FieldTurf, which is fast.

BEHIND THE CURTAIN

The Combine was a private event before it was first shown on television in 2004, thanks mainly to the launch of NFL Network.

Previously, media and cameras were prohibited. When I began attending in the mid-’90s, only about eight to ten reporters were present. This is where the late, great John Clayton thrived, creating a valuable information network. Others included Peter King and John Czarnecki, the behind-the-scenes fact man who kept CBS and then FOX credible.

There were no credentials and no planned interviews. We loitered in hotel lobbies or a few popular bars to “bump into” scouts, coaches, and team officials. The Martini Bar. The Cigar Bar (cough, cough). If you had had a decent expense account, there was (and is) St. Elmo’s Steak House. Be careful of their giant shrimp (an oxymoron?) — they are hot. Some of us dressed in running suits similar to those worn by scouts and just walked into the stadium to watch workouts.

That ended in about 2000, when dozens, then hundreds, and now thousands of media realized this was a great chance to meet with team leaders and, eventually, see the workouts. However, the media was prevented from seeing workouts until a few years after the NFL Network began broadcasting. Credentials are as complicated as those for a Super Bowl. Getting a room in a hotel is both difficult and expensive.

For a while, I was fortunate enough to make the annual trek to Indianapolis on the Madden Cruiser. It was a two-day-plus, nonstop journey, except for the out-of-the-way Mexican restaurants we visited. John kept the temperature barely above freezing, which usually prepared me for Indianapolis. While I covered the Combine, Madden attended meetings, often with the Competition Committee. When it was time to leave, he gave about a one-hour notice, so unpacking wasn’t practical.

On the way back, we would watch the Combine workouts on the big-screen TV on the bus, and he would leaf through a binder of information from NFL Draft Scout. Those were great days. I miss him all the time.

In 2004, after the NFL began scheduling interviews with players and team officials, NFL Draft Scout, working with the Pro Football Writers of America, created a method for certified PFWA members to exchange transcripts electronically—the collaborative effort handled as many as 300 interviews. Signups for 2025 transcripts began Monday, and interviews were scheduled to begin Tuesday.

Although there has been talk about moving the Combine from Indianapolis, the NFL’s contract extension with the city now goes through 2026. It would be difficult to match the amenities at Indy, especially the availability of medical outlets to check the players — which was the initial reason for a Combine even before they added the “Underwear Olympics,” including the 40-yard dash.

Oh, right. the 40. Let’s get back to that.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

The Al : Fitting Trophy for best Combine 40-yard time

Like Al Davis himself, the Combine’s 40-yard dash has long been mysterious.

At NFL Draft Scout, Brian “Hitman” Hitterman has many abilities, including rating players better than most teams and estimating 40-yard times with eerie accuracy by watching them play. A former college linebacker himself, Hitterman built and maintains our vast database from the beginning of the Indy Combines.

One thing is sure: the existence of a consistent, official time in the 40-yard dash is a total myth, especially when comparing different decades.

Each player (usually) runs the 40 twice. His time is registered by at least two, often three methods.

Electronic times (ET) are initiated by lifting the hand from a pressure mat and stopped by the torso passing through an infrared beam. They are also timed at 10 and 20-yard intervals.

Hand-Held times (HH) initiated timing on first movement of the player from a 3-point stance, with a stopwatch and stopped with a laser at 40 yards. Again, they are also timed at 10 and 20-yard intervals.

Fully automated times (FAT) is used in the Olympics, with the runner’s start and finish timed electronically without human intervention. The Olympics have the added element of a starting gun, which creates a time margin. This method, with electronics detecting start (no gun), was tested and rejected at the Combine. The times were so slow, an average of 1.22 seconds, that they would have created a culture shock. A 4.30 would become a 4.52. A 4.50 would be a 4.72.

Based on NFL Draft Scout records, the Combine seemed to vacillate for years on if there was even a so-called official time. In reality, they reported all four results — two HH and two ET — and the teams did what they wanted. Some teams positioned scouts in the stands to time the runners. Some teams averaged all four or the fastest and slowest. Nothing was actually official. That became a media invention.

When NFL Network began televising the 40-yard dash in 2004, Combine execs had to decide something to tell viewers. For a while, there were plenty of questionable “official” times reported by NFL Network and eventually NFL.com.

Mike Weinstein has a degree in mechanical engineering and is the founder of Zybek Sports, which set the standard for timing athletes since 2008 at the Combine. Each year, he times thousands of athletes, including those in prep and youth leagues. He noted that there is a disparity between hand-held and "electronic" time of between .04 and 1.02 seconds. That's a lot when teams bet millions of dollars on a draft pick.

His mechanisms yield both HH and ET results.

For years at NFL Draft Scout, we gave the player the benefit of the doubt and listed his fastest time, regardless of the method. Eventually, we settled on using ET results because that was what NFL Network and NFL.com usually portrayed as “official.” Their production is still a bit mystifying because players are timed on the screen during the run and the result is declared unofficial, despite the fact it is synced up with Weinstein’s ET mechanism. After a few minutes they announce an “official time.”

Remember Xavier Worthy’s “record” time of 4.21 seconds last year? That 4.21 was Worthy's best electronic time. His best hand-held time was 4.20. For what it's worth, the time that is really the best in Combine history, regardless of methodology, is 4.16 seconds. That was the best hand-held result for Kent State's Dri Archer in 2014. His official time, however, was 4.26 seconds, his best ET. Yes, that’s a full tenth of a second slower, but “official” is “official,” right?

Last year, NFL Draft Scout charted all 219 players who ran the 40 at the Combine, using HH and ET times taken on the same runs. The chart showed of 219 runs, 157 were faster by HH. Otherwise, 43 were slower by an average of .01 seconds, and 19 were the same.

Dan Pompei, a great journalist, writer, and fellow selector for Pro Football Hall of Fame, commemorated Al Davis’ love for fast players in a 2014 story for Bleacher Report. You’ll find Pompei with The Athletic now, but that Davis story from over a decade ago is a must-read.

Pompei recounted how Davis became infatuated with speed as a young fan of his neighborhood Brooklyn Dodgers and how their daring base-running kept opponents on edge. Davis admired the Yankees for their power and size and the Dodgers for their speed.

"The Dodgers…were different," Davis said in 1991."They believed in speed and development and were willing to take chances."

Davis wanted opponents to fear the Raiders' speed.

"You make sure the opposing defense goes to bed the night before the game knowing, fearing that they will be facing somebody who can beat them deep on any play," Davis said in the book Fire in the Iceman by Tom Flores and Frank Cooney. "Let them stay awake all night worrying about it."

Thanks for the mention, Dan. Tell me more:

Pompei: To understand the Raiders' obsession with speed, you have to go back to 1963. That's when Davis arrived in Oakland as a 33-year-old head coach and general manager with all kinds of ideas bubbling beneath a great head of hair.

One of those ideas, as described in the book Fire in the Iceman, was to acquire deep threat Art Powell. The wide receiver had a big season for the New York Titans (to become the Jets) in 1962, but he played out his option and secretly signed with the Bills. Concerned that they might have to compensate the Titans, the Bills stalled on submitting the contract to the league. That's when Davis swooped in, traveling to Powell's home in Toronto, signing him and leaving the Bills with a worthless contract.

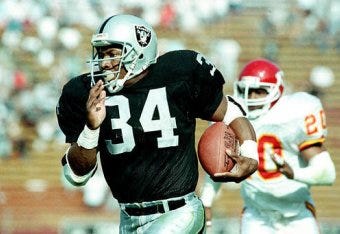

Over time, Davis would show an affinity for fast running backs as well as tight ends and wide receivers. Among the running backs he would acquire was Bo Jackson, who ran a 4.12-second 40-yard dash in 1986. Of Jackson, Ron Wolf said: "He was the fastest guy I ever saw, even at 239 pounds."

If a player was speed-deficient, Davis didn't even consider him. It didn't matter if he was a playmaker. He had to run fast. It was an edict that didn’t always work.

Per Pompei:

In 1969, some of the Raiders scouts were high on a lanky stand-up defensive end out of the University of Miami, but they couldn't get Davis to consider Ted Hendricks because he ran a 5.1 40-yard dash at the Senior Bowl, Wolf said.

After watching Hendricks dominate at linebacker for the Baltimore Colts and Green Bay Packers, Davis changed his mind and gave up two first-round picks in a 1975 trade to acquire the future Hall of Famer.

With Davis driving hard, the Raiders kept getting faster. And better. They would be back to the Super Bowl three times in eight years, starting with the 1976 season. And they would win three Lombardi Trophies.

To understand the Raiders' obsession with speed, you have to go back to 1972. That's when the Raiders drafted Cliff Branch out of Colorado in the fourth round, even though he had caught only 13 passes the season before. What attracted Davis was Branch's time of 10.0 in the 100 meters in the NCAA Championships.

"He was the original if he's even, he's leavin' guy," Wolf said. "It was unbelievable how fast he was."

How fast? Sadly, we never got a 40-yard time on Branch. But he did run that 100 meters in 10.0 — ten seconds flat. And he played well enough to get three Super Bowl rings and be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Jim Hines is the only NFL players who broke the 10-second barrier in 100 meters. Hines was clocked in 9.95 seconds to win the 1968 100m Gold Medal in the Mexico City Olympics. But in two seasons with the Miami Dolphins and Kansas City Chiefs, he caught only two passes and earned the nickname “Oops.” Trindon Holiday, a 5-5 return specialist, was the only other NFL player with a 10.0 time in 100 meters.

In his third season, Branch caught 13 touchdown passes and was named first-team All-Pro. The Raiders' success with him was intoxicating for Davis. This is where the speed obsession might have started to be counterproductive.

"It may have led to a mindset that if I was successful with this guy, I could do it with that guy," Raider personnel director Jon Kingdon said of Davis. "But in many ways, Cliff was an exception. Sometimes it would work, sometimes it wouldn't."

Pompei counted the ways:

Among the players who failed to play up to their 40 times for the Raiders were Vance Muller (4.32 40-yard dash), Alexander Wright (4.14) and Raghib "Rocket" Ismail (4.28). In 1990, the Raiders had two Olympic gold medal winners on the roster in Sam Graddy and Ron Brown, and a third player with Olympic-caliber speed in Willie Gault. Only Gault could effectively translate his speed to the football field.

In the sunset of Davis' career, he drafted Stanford Routt (4.27 official time), Darren McFadden (4.33), Darrius Heyward-Bey (4.30), Jacoby Ford (4.28), DeMarcus Van Dyke (4.28) and Taiwan Jones (4.33). His final draft choice was quarterback Terrelle Pryor, who ran a 4.36.

When he passed away in October of 2011, Davis was still seeking the next Cliff Branch. And, again, in my mind’s eye, Al will be there this week, sitting with Gil Brandt, looking for the fastest player in the Combine.

We already have the Vince Lombardi Trophy for the Super Bowl winner, the George Halas Trophy for the NFC champion, and the Lamar Hunt Trophy for the AFC champion. Al Davis is the only person in NFL history to be a head coach, a commissioner, and a team owner.

Let’s award something befitting his contribution and passion for the game. Call it the Al Trophy and give it to the player with the fastest 40-yard time at each Combine.

What a great read Frank! Had a chance to ask Gil about that Bo 40-time: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d45xR1mj2aU

Fantastic history and context to the evolution of the Combine - a must-read if folks want to understand the how and why beyond the flashy what and the obvious who-where-when.

Al certainly was a visionary specific to the growth potential of the NFL in many forums.