Welcome to a discussion that was more than 50 years in the making. Let us take you back.

This year, the controversial but compelling potential collision of Jim Plunkett and another Manning, this time Eli, is already creating a stir. Social media is all over it, and Pro Football Hall of Fame selectors are receiving strongly worded “advice” about each player.

So, let’s address it out loud now before someone else tries. We know more than most about the tangled and tortured background because we closely covered the key participants before and after the 1971 draft. That’s when the seed for this year’s debate was planted as Plunkett and Manning patriarch Archie were selected 1–2.

Remember? Oh, right, that was before ESPN. You might need to resort to YouTube.

It was the first Year of the Quarterback draft in the 20th Century, predating the celebrated 1983 event by a dozen years. It featured, among others, Plunkett, Manning, Dan Pastorini, and a Notre Dame prospect whose PR guy changed the pronunciation of the players’s last name from “Theesman” to Theisman to rhyme with the Heisman Trophy.

He didn’t win it, but the name stuck, although we just called him Joe. Still, such a brash move reflects the intensity among quarterbacks that year, although nobody expected the ramifications of that draft to last until now. We will get back to the details of that draft later.

Din for Plunkett is loudest

The Plunkett-Manning topic was rejuvenated as soon as former New York Giants quarterback Eli Manning became eligible for the 2025 class. Campaigns erupted to put him into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as a first-ballot inductee.

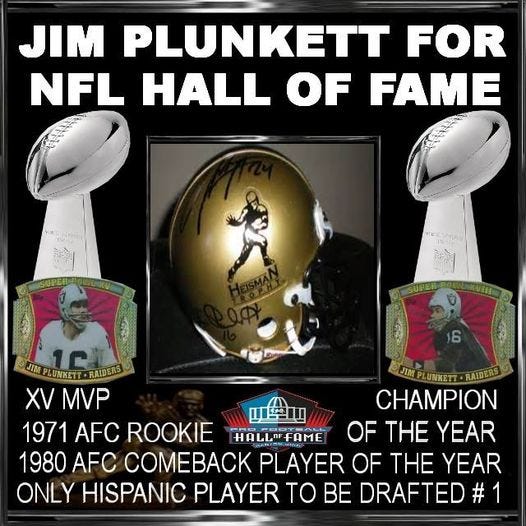

But whether it is the first ballot or any ballot, the Manning backers have a long way to go compared to the decades-long crescendo of cries to induct Plunkett, the former Patriots, 49ers, and, importantly, Raiders quarterback.

Based on extended public outcry, Plunkett leads all others—and I mean all others—with the din of fans screaming to get their guy into the Hall. Sure, the ubiquitous Raider Nation leads the charge, but as a selector on the Hall of Fame senior committee, I’ve received messages from all manner of fans, including politicians, former players, coaches, the Raiders' front office, the Latin community, and … did I say the Raiders’ front office? The Raiders made their point in an eight-page brochure that they distributed to the selection committee.

Execs at the HOF confirm that, over time, Plunkett received more outside support than any other player. That’s saying something, considering Plunkett was never even officially discussed in a selection meeting. Never.

Plunkett’s vociferous backers base their argument on the fact that he won two Super Bowls, which means he absolutely belongs in the Hall, right? Hold that thought.

New Yorkers are adamant that Eli Manning should be a Hall of Famer because — wait for it, wait for it — he won two Super Bowls. Do we sense a trend here?

Based largely on that commonality, these two are expected to be enmeshed in a strange face-off, despite coming into the Hall of Fame world from two widely different directions. They will vie for votes against each other ONLY if they both become finalists for a spot in a talent-laden battle to enter the Class of 2025. Can you say long shot?

After retiring five years ago, this is Manning’s first year of eligibility, so he is in the running for a spot in the Modern Era class.

In stark contrast, this is Plunkett’s 33rd year of eligibility, during which time he made the list 20 times as a Modern Era preliminary candidate but nothing since. So, the selection committee has never formally discussed him, even as a semifinalist.

Plunkett and the Manning patriarch

Early rumblings indicate Plunkett will return to at least the preliminary list for the Senior Class of 2025, his first appearance since 2011. Maybe his return was encouraged by the presence of Manning, a fellow dual Super Bowl winner.

As we will see, these men share significant similarities. But even more interesting is their profound differences.

What could come of a Manning-Plunkett discussion?

It may reveal they both belong in the Hall of Fame.

It may show that neither of them should be in the Hall of Fame.

Maybe one should go in and the other not.

And, well, who the hell knows? There is no magic formula, and always more questions than answers.

Their connection is curious because it goes back 53 years to when Plunkett and that other Manning were headliners in the 1971 draft.

After ascending from defensive end to quarterback in a dazzling career at Stanford, Plunkett entered the 1971 NFL draft fresh off upsetting Archie, the Ole Miss folk hero, to win the Heisman.

Yes, that would be Eli’s father, the patriarch of a football family that includes HOFamer Peyton and extends down to Texas sophomore quarterback Arch Manning.

That 1971 draft set the stage for the respective careers of our two subjects.

Follow along …

Plunkett was drafted No. 1 by the newly renamed New England Patriots. The New Orleans Saints then grabbed Archie Manning at No. 2. Pastorini, from the University of Santa Clara, was the No. 3 quarterback selected — by Houston. Remember that. He will play a crucial role in this convoluted plot.

Both Plunkett and Archie Manning suffered greatly during their time with the teams that drafted them. Archie spent 11 horrific years shackled to the Saints when there was no escape via free agency. Despite being regarded as an excellent quarterback—then and now—Archie’s best season with the Saints was 1979, when the team was 8-8, and he was named to one of his only two Pro Bowls.

Eli intent on avoiding fate of father, Plunkett

Eli knew his dad’s story all too well, and when he was projected to be the No. 1 pick in 2004, the younger Manning didn’t want to see history repeated. More than a week before the draft, Eli told the Chargers that he would not sign with them if they drafted him. He wanted a say in his landing spot.

Meanwhile, the Giants wanted Eli—and vice versa—but the New York team picked No. 4. The Chargers made a Wall Street gamble by snatching Manning No. 1 and holding him hostage as his value rose quickly in New York. An hour later, in a pre-arranged ploy, the Giants drafted North Carolina State quarterback Philip Rivers, setting the stage for a historic trade.

The Chargers sent Manning to the Giants for a pair of 2005 draft picks — and Rivers, thereby tying those two quarterbacks (Rivers and Eli) together for eternity. Rivers’ prolific 17-year career ended in 2020, and he will be eligible for the HOFame in 2026. If Eli isn’t granted a first-year induction in 2025, he and Rivers will be the big debate for the 2026 Class.

Back to our original dynamic duo. The point of those draft stories is that while Eli choreographed his entry to the NFL, Plunkett, like Archie, was the victim decades before of a cruel system capable of destroying potentially great careers.

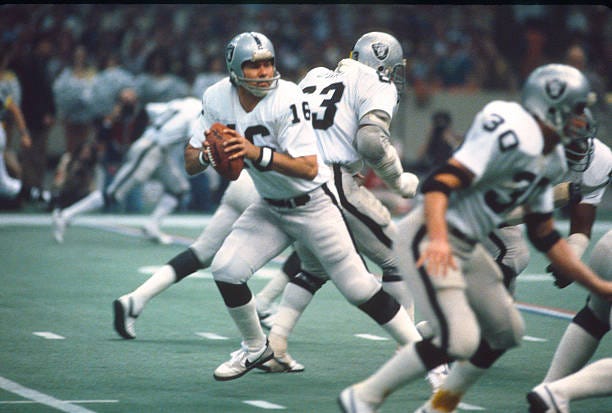

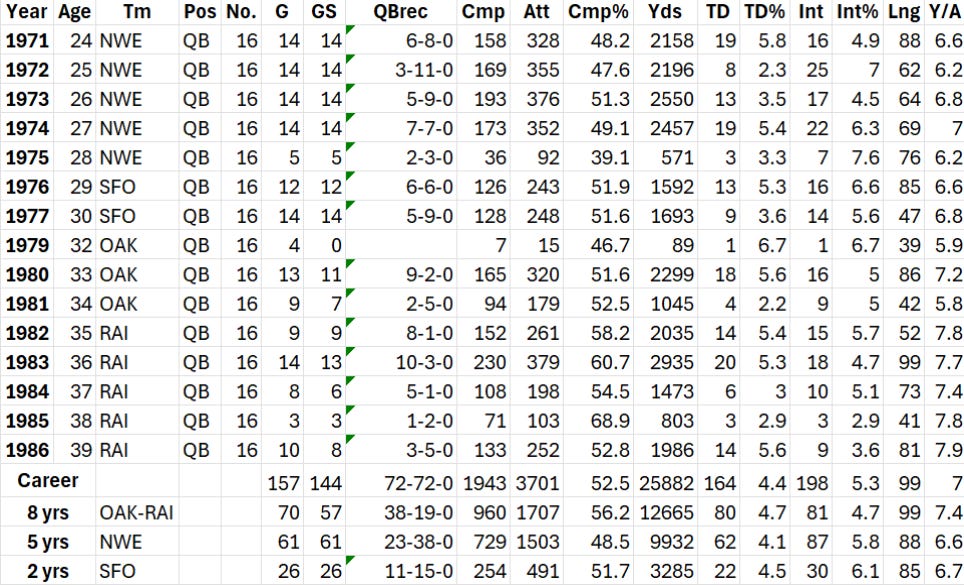

In Plunkett’s first season (1971), he started all 14 games, threw for 2,158 yards and 19 touchdowns, threw 16 interceptions and was named Rookie of the Year by UPI and The Sporting News. In Eli Manning’s first year (2004), he started seven games (16-game season) and threw for 1,043 yards, six touchdowns, and nine interceptions.

After that, Plunkett’s early career spiraled downward as he endured college-style coaching by Chuck Fairbanks, who ran the option even when his quarterback was in his first game back after a plastic screw was installed in his shoulder. By the end of 1975, Plunkett was a physical wreck following multiple shoulder and knee surgeries; his record was 34-53.

He was shipped to the San Francisco 49ers, who were even worse. Plunkett was battered for two chaotic seasons with SF and managed an 11-15 record. Before the 1978 season, the 49ers waived Plunkett. The former Heisman Trophy winner and No. 1 overall pick only seven years earlier cleared waivers. Nobody wanted him, and he went to his home near Stanford, fought off depression, and pondered his future. We will leave Plunkett there pondering and get back to him later.

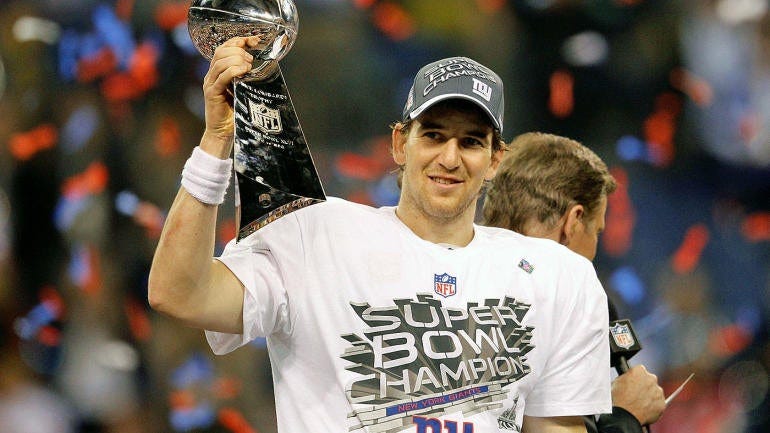

During a similar phase of Manning’s career, he alternated between extremely good and so-so. But he was on top of the hill when he and the Giants upset the vaunted 18-0 New England Patriots, 17-14, in Super Bowl XLII.

That game featured one of the most memorable plays in history, known as the “Helmet Catch.” In it, Manning escaped the clutches of several Pats defenders and lofted the ball downfield, where wide receiver David Tyree, under attack from safety Rodney Harrison, managed to pin the ball against his helmet. It was a 32-yard gain that continued what proved to be the winning touchdown drive.

The Giants and Manning went 30-18 the next three seasons before meeting the Pats in Super Bowl XLVI. This time, Mario Manningham made a spectacular 38-yard catch to set up the winning score, 21-17. Manning picked up his second Super Bowl MVP.

After that, Manning managed only two winning seasons for the rest of his career, compiling a 49-67 record in his final eight years. Some said he hurt his legacy by hanging around too long. It also allowed time for some to say he was two miraculous Super Bowl catches away from being just another New York sports footnote.

Plunkett rebounds with Raiders

And what about Plunkett, the unwanted former Heisman winner sitting home pondering his future?

Here is an excerpt from Fire in the Iceman, the autobiography I co-authored with future Raiders Hall of Fame coach Tom Flores. It discusses the key characters in that 1971 draft, reiterates some of our earlier comments, and adds deeper insight and information about the aftermath.

Archie Manning got the worst of it. Although most people in football recognize that he may have been one of the best quarterbacks ever to play the game, Archie suffered through his entire career with bad teams at New Orleans.

Plunkett was in on every offensive snap his first season and was named the NFL's Offensive Rookie of the Year. When I became an assistant coach with the Raiders we played against the New England Patriots, and I got to see first hand how atrociously they were treating Plunkett. Here was a guy perfectly suited to be a strong, drop-back passer and Patriots coach Chuck Fairbanks was using Plunkett to run the option. Not a run-pass option, mind you, but a run-run option, where the quarterback elects whether to pitch to a back or keep it himself …

I remember one game the Patriots had against the Raiders at Oakland when Plunkett ran the option and was wide open with nothing but field in front of him and suddenly he pulled up like he was shot. He pulled a hamstring and had to go out of the game. He was beating the hell out of us, but he spent the rest of the game on the bench and the Raiders pulled out a victory, Eventually he injured and then re-injured his shoulder running that stupid option play. His confidence and his effectiveness were also injured.

In 1976 the 49ers, under the new ownership of Eddie DeBartolo Jr., got Plunkett from the Patriots for quarterback Tom Owen and four draft choices, two firsts that year and a first and second in 1977. Then the Niners, who were trying to rebuild, put him on the field with very little real help and things got even worse.

By 1978 Plunkett was a remnant of the guy I watched win the Rose Bowl for Stanford. You could see his passing motion was altered and his confidence was gone. He didn't throw the ball so much as he pushed it, kind of like a shot putter. In a preseason game against the Raiders he threw 11 consecutive incompletions and some of them we so far off target if was difficult to tell who was his intended target. Not long after that the 49ers waived him. The former Heisman Trophy winner and Rookie of the Year was not even claimed and became a free agent.

Ron Wolf, one of the best personnel men in the league, scheduled Plunkett to work out for the Raiders at our facility in Alameda. John Madden asked me if I would work him out. So Al Davis, Wolf and Madden stood on the edge of the field while Lew Erber, another assistant coach, and I put Plunkett through the usual hoops, looking for movement, throwing on the move, scrambling, throwing for distance, touch.

After watching his horrible performance against the Raiders in that preseason game, I was curious about his physical ability. Before that workout, I admit I had my doubts. When I'm working out a quarterback I like to stand downfield about 25 or 30 yards to see if there's any zip on the ball. Sometimes you can be misled if you don't catch it.

That's my way of getting a feel. Sometimes the ball is thrown too hard, sometimes too soft and sometimes just right.

There are some guys you would hate to play catch with. I hated to catch Daryle Lamonica's passes because, for some reason, his passes hurt my hands. My passes were always kind of soft, although they traveled at good speeds and got there quickly. Snake's were the same way, soft and easy to catch. Plunkett's were kind of in between, good velocity but not hard to catch. I was impressed.

“There’s nothing wrong with him physically that I can see,” I said.

The Raiders signed Plunkett to a three-year deal, but Madden made it clear that the former Stanford star would not play in a game. Plunkett’s only action in 1978 was mimicking opposing quarterbacks in practice.

Madden retired after the 1978 season, only 42 years old but wracked by ulcers. Flores became head coach. The 1979 season began with fan favorite Ken Stabler and owner Al Davis feuding, and Snake took his time before showing up at training camp. The Raiders missed the playoffs a second straight year, and before the 1980 season, Davis traded Stabler to Houston for the Oilers’ starting quarterback Dan Pastorini. Remember him from that 1971 draft?

Plunkett and Pastorini had a history. They were prep stars from different sides of the tracks in San Jose. Pastorini was hyped as a great quarterback from Catholic football powerhouse Bellarmine, and Plunkett played for James Lick, a public school on the poor side of San Jose. He didn’t get as many headlines as Pastorini, but he did get a lot of attention when it became known both of his parents were blind.

Personality-wise, Pastorini and Plunkett were like oil and water. When they were thrown together with side-by-side lockers, Plunkett said they “succeeded in creating an air of amiability, though it was only thin air.”

On the field, Raiders players and coaches were impressed with Plunkett at training camp in 1979 when Stabler was holding out. Some whispered that Plunkett had a better training camp than Stabler.

Blasphemy? Nope. Flores verified that in his autobiography:

All things being equal, there would have been times during the 1979 season that Plunkett would have replaced Stabler. But all things weren't equal. Yes, it was obvious that Jim had regained his passing touch. But Stabler was the team leader.

After Pastorini arrived in 1980, everybody knew he would be No. 1 because the team gave up Stabler to get him. But to those of us who watched training camp that year, it was obvious that Plunkett was the better quarterback.

I talked with Davis during that camp, asking how Pastorini was doing, especially in comparison to Plunkett.

“I like them both,” he said. “I like having two quarterbacks who can throw deep. These things have a way of working their way out.”

More prophetic words were never uttered. Except for when Plunkett asked Davis to be traded. Davis waved him off, saying, “Just be prepared.”

Going into the fifth game of the 1980 season, the Raiders were 2-2, Flores thought he was about to be replaced by Sid Gilman, and Plunkett was unhappy on the bench and thought he should be starting.

That all changed in a snap. Unfortunately for Pastorini, the snap was his right tibia cracking under the weight of Kansas City Chiefs lineman Dino Mangiero.

Plunkett took over at quarterback. Few realized this was a turning point for Plunkett, Flores, and the Raiders franchise.

Plunkett was not an immediate success. Kansas City led 31-0 in the second quarter. Five sacks and five interceptions thwarted Plunkett’s attempt at a comeback, as he set a Raider record by throwing 52 passes, completing 20. The Chiefs held on to win, 31-17.

The Raiders were 2-3, and Plunkett was finally the starter. Guard Gene Upshaw, team captain, future Hall of Famer, and union leader, called for one of those players-only meetings. He told me the offensive line had more confidence in Plunkett, so he expected things to improve. Uppy always had a good feel for his team.

What happened after that is well documented. The Raiders won their next six games and nine of the remaining 11 in the regular season to finish 11-5. Then, they swept through the playoffs to become the first wild card team to win a Super Bowl with a 27-10 upset of the Philadelphia Eagles.

Plunkett threw for 2,299 yards, 18 touchdowns, and 16 interceptions after coming off the bench in 1980. He was named Comeback Player of the Year and MVP of Super Bowl XV.

Despite the presence of QB Marc Wilson, a first-round pick out of BYU in 1980, Plunkett endured and started 13 of 14 games in 1983. The Raiders won one of the most lop-sided upsets in Super Bowl history with a 38-9 beatdown of the highly favored Washington team, now known as the Commanders.

Plunkett’s record in his last eight seasons was 38-19, a .667 average. That is better than any eight-season stretch in Manning’s career and certainly better than that 49-67 record in his final eight seasons. Plunkett was also 8-2 in the postseason compared to Manning’s 8-3.

This is only part of the puzzle.

Both finished with a .500 record, Plunkett at 72-72 and Manning at 117-117.

Neither player was ever selected as a first- or second-team All-Pro, but Manning was named to the Pro Bowl four times. Manning was Super Bowl MVP twice, and Plunkett once. Plunkett also won Rookie of the Year (1971) and Comeback Player of the Year (1980).

So much for the honors and jewelry. Let’s respect football as the ultimate team game and look at their respective teammates.

Future Hall of Famers surrounded Plunkett. Of course, Al Davis was the Hall of Famer at the top. In Super Bowl XV, there was coach Flores, Upshaw, tackle Art Shell, wide receiver Cliff Branch, linebacker Ted Hendricks, and punter Ray Guy. By SB XVIII, Plunkett again had Flores, Branch, Hendricks, and Guy, with the addition of defensive end Howie Long, cornerback Mike Haynes, and running back Marcus Allen, who literally ran away with the MVP honor in SBVIII.

That is a fist full—ten!

By contrast, Manning’s list of Hall of Fame teammates in his two Super Bowl wins shows only one defensive lineman — future TV host Michael Strahan.

Plunkett had six coaches in his NFL career, including Hall of Famers Madden and Flores. Manning ultimately had three coaches but played his first 12 years under Tom Coughlin. Ironically, Coughlin’s strong card to become a Hall of Famer is that he won two Super Bowls with Manning at quarterback.

So there it is. What is your call? Manning? Plunkett? Both? Neither? Wait ‘til next year?

To be continued …

Plunkett’s Career Stats — Regular season only:

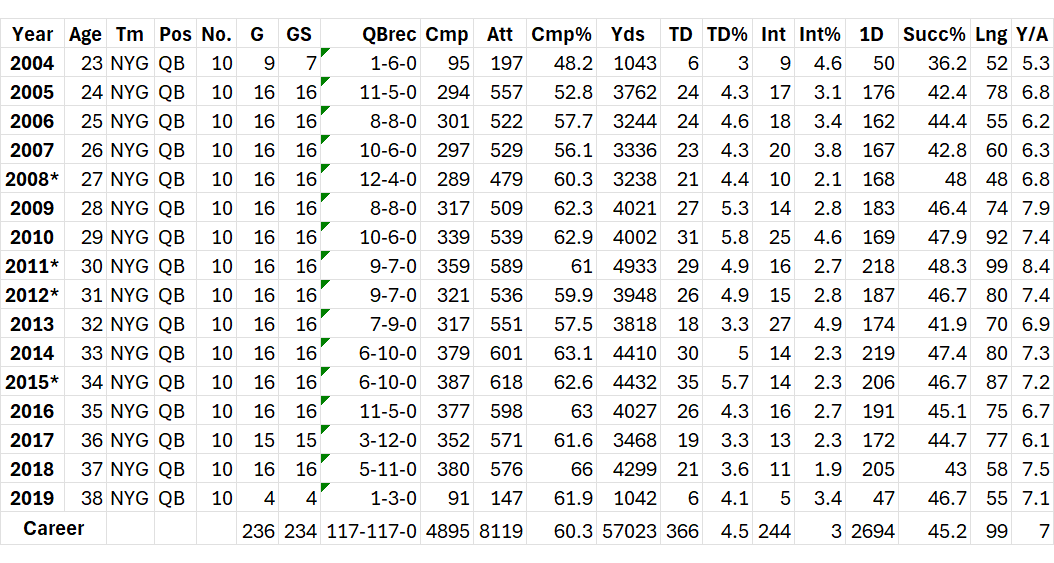

Manning’s Career Stats — Regular season only:

What a fun article. Connected some interesting dots too!

Btw … neither!

Manning will probably go in before Plunkett. But when he does, that all but guarantees Plunkett follows.

Signed, a hopeful Raiders fan.