🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

(Editor’s Note: This is part of a series on the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s journey to select the Class of 2026. It is written by Frank Cooney, a long-time Seniors Blue Ribbon Selection Committee member in his 33rd year as a selector. The Hall of Football is not affiliated with the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Opinions expressed are those of the Hall of Football [HallofFootball.substack.com)

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

We are now waiting to hear the results of significant cutdowns for the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s 2026 Class. The Seniors Blue-Ribbon Committee is trimming its list of 52 to 25 and the full committee will cut the Modern-Era roster from 52 to 25.

The guidelines for this huge task are daunting — there aren’t any, really.

The Hall of Fame’s sole rule is to consider only what happens on the football field. But selectors allow the definition of that guideline to be skewed by other factors, including off-field activity that they insist impacts action on the field.

Despite efforts by HOF execs, this uneven application often gains a foothold. It is flawed, bothersome and uncomfortable in an era that is supposed to be more socially sensitive and should be more historically educated. But I question if either is a factor.

It seems the overriding guideline, albeit subliminal in many cases, is likeability. I will address this across all categories of the Hall of Fame in another story that includes names of benefactors and victims.

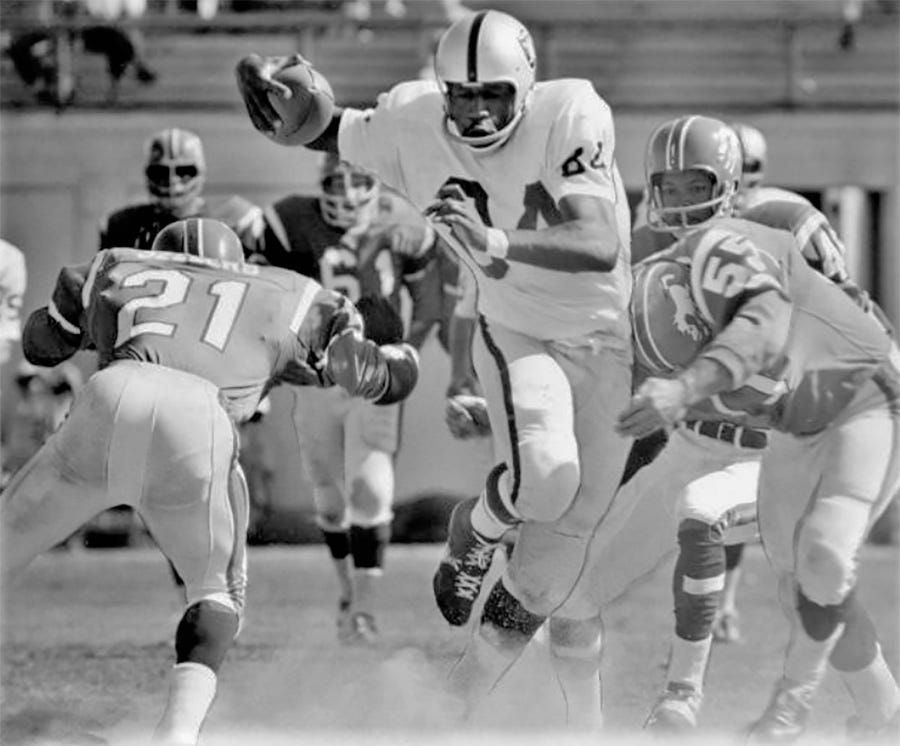

I should have learned this when I first joined the Selection Committee 33 years ago and suggested we should discuss wide receiver Art Powell. A couple of veteran selectors cornered me, with one saying, “We don’t want that uppity n***** in the Hall of Fame.”

I was reminded that he married a white woman in 1957 and was blackballed by the NFL in 1960 for threatening to boycott a game that would treat Black players differently than their teammates. Two more times he threatened to boycott, leading to both games being relocated. They made it clear they felt such actions nullified his worthiness for the Hall of Fame.

I knew the reality of those stories, but also knew Powell’s play on the field had a huge impact on pro football in the 1960s. As the newest, youngest member of the committee, with social values that reflected a liberal background on the left coast, I was shocked but felt outnumbered and outgunned by well-known selectors decades older than me.

So it wasn’t until 2023, some 30 years later, that I again advocated for Powell. By then I was the most senior selector and a member of the Seniors Committee. The country had been through the pandemic and yet another round of social unrest that I thought might have enlightened the selectors.

Still, I approached this nomination by first citing only his achievements on the field, which were more than HOF-worthy. For historical perspective, I also included his fight against segregation.

If the growing “woke” movement influenced selectors, the results were difficult to discern. Both Powell and former coach Buddy Parker were among the finalists for the 2024 Class. In a rare result, both Powell and Parker failed to get the necessary 80 percent thumbs up to be inducted. To some there seemed to be an irony that Powell’s social awareness was ahead of its time while Parker was dinged for his role — perceived or otherwise — in the Detroit Lions’ racial imbalance.

I believe Powell’s anti-segregation activity during the Jim Crow era was not a factor in 2024. He was not inducted because too few selectors not on the Seniors Committee — which I inundated with facts and stats — knew much about Powell, and admitted as much in a debriefing after the vote.

After Powell was rejected as a finalist, new processes imposed limitations that hinder a Senior player’s path to induction. I opted not to actively advocate for him last year. But when wide receiver Shannon Sharpe was inducted as a Senior I was compelled to point out Powell’s similarity to the former Green Bay star.

Hardcore fans and professional historians knew of Powell’s greatness. But the multiple sessions I spent talking to the Seniors Committee didn’t carry over in the five-minute presentation to the full group, where recency bias is rampant. Powell’s career was over by 1968, long before ESPN or NFL Network.

And in a new move by the HOF, members of subcommittees — Senior players, Coaches, Contributors — will be rotated to get all 50 selectors involved. So this is the first time in more than a decade I am not on the Seniors Committee. So I make my points here.

Powell’s story was remarkable on the field and historical off it. Hall of Fame coach Bill Walsh called him “a man and a player ahead of his time.”

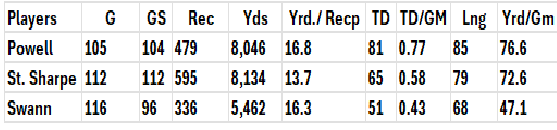

But how can we convey that? Statistics are tricky. But the induction of Sharpe, who played until 1994, might help bridge the gap to Powell. Powell and Sharpe shared one issue, a relatively short career of nine seasons, 105 and 112 games respectively. Previously, Lynn Swann was inducted after a career of nine seasons, 116 games.

Technically, Powell is listed as playing 10 seasons and 117 games. However, in his rookie season, the Philadelphia Eagles signed him to an incentive-laden contract as a wide receiver, but played him only at safety and returner. We dismissed the 12 games in that season, although he finished No. 2 in kickoff returns and made three interceptions.

In this chart, we compare Powell to Sharpe and Swann, two Hall of Famers with similar careers. Playing in fewer games, Powell averaged more yards per reception than both, scored six more touchdowns than Sharpe, 30 more than Swann and averaged more touchdowns and yards per game than the HOFamers. In fact, in the history of pro football, only Don Hutson averaged more touchdowns per game, which we show in a later chart.

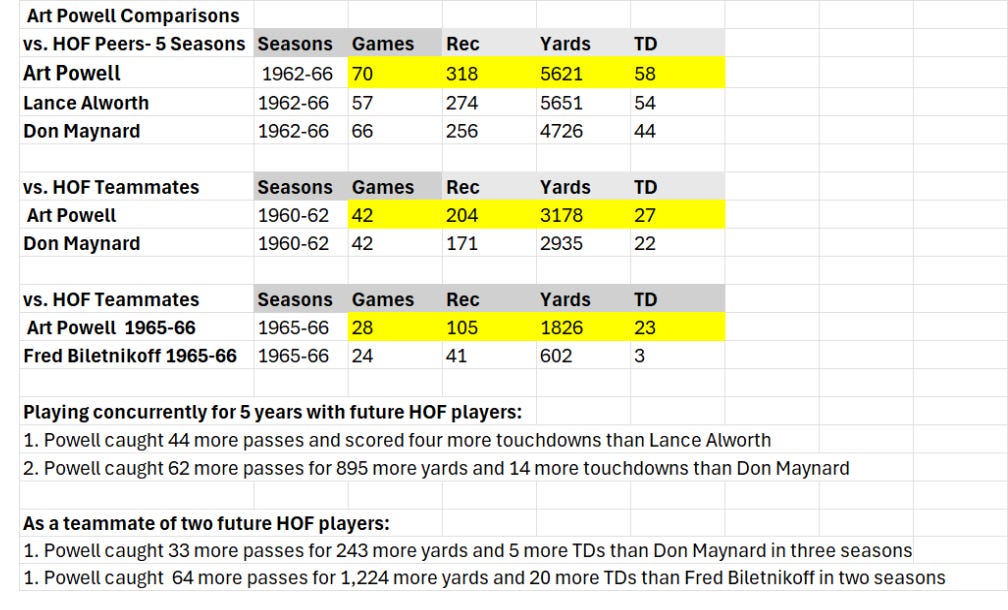

Now let’s compare Powell with three of his iconic contemporaries.

Powell was a teammate of two future Hall of Fame wide receivers — Don Maynard and Fred Biletnikoff. In 1960, Powell and Maynard became the first teammates to each catch passes for at least 1,000 yards. They did it again in 1962.

But in their three seasons playing for what became the New York Jets, Powell caught 33 more passes for 243 more yards and five more TDs than Maynard. With the Oakland Raiders in 1965-66, Powell caught 64 more passes for 1,224 more yards and 20 more TDs than Biletnikoff.

Not even close, right? But wait, there’s more.

Powell also played five years (1962–66) simultaneously with legendary Hall of Famers Lance Alworth and, of course, Maynard. During that time, Powell caught 44 more passes and scored four more touchdowns than Alworth, and had 62 more receptions, 895 more yards and 13 more touchdowns than Maynard.

It is easy to see in this chart:

Powell vs. HOF teammates and peers

Powell’s career realistically ended in 1968 due to a knee injury, while Biletnikoff, Maynard and Alworth played a few more seasons. However, this comparison shows Powell’s relative productivity, juxtaposed to well-known future HOF players. The others marched right into the Hall of Fame. Looking at this, it appears he should have done the same.

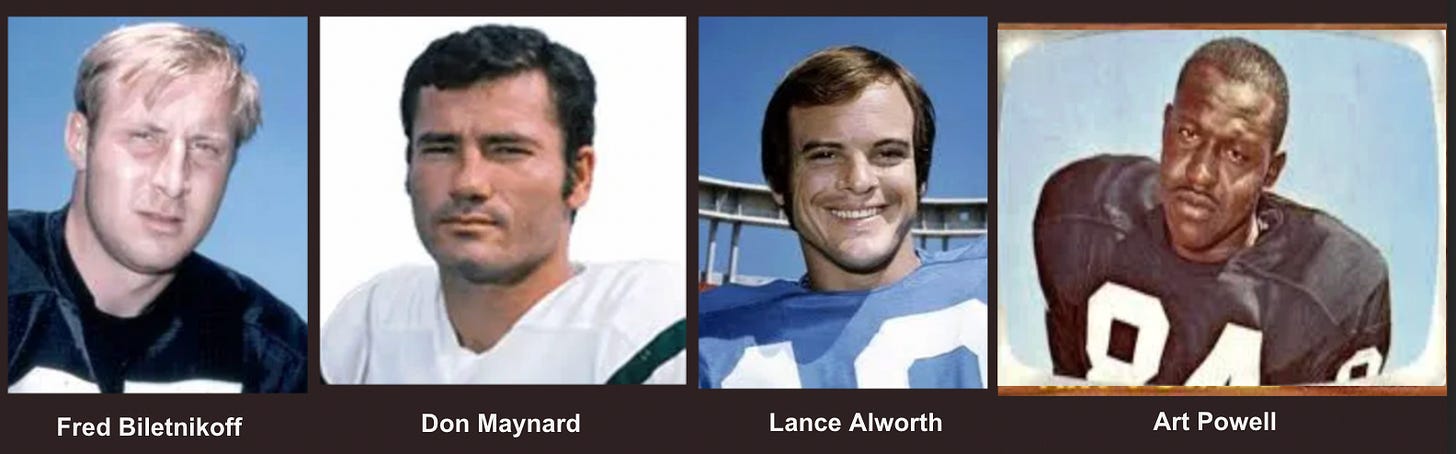

It’s right there — in black and white. Below are pictures of the four top wide receivers from the 1960s. Which one of these is not like the others, not counting being in the Hall of Fame?

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

Now let’s update Powell’s standing among wide receivers in the game’s history.

Summarizing, Powell is:

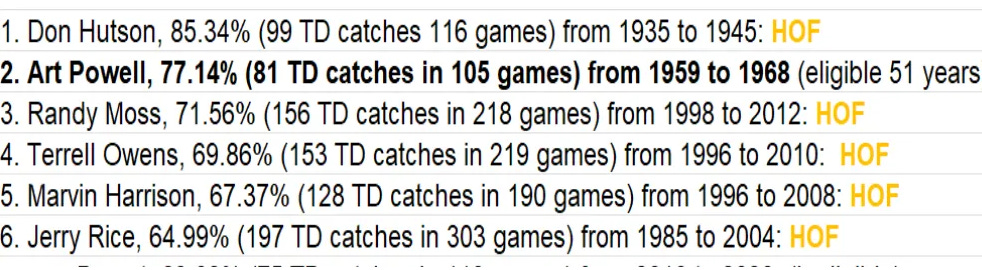

No. 2 in touchdown catches per game (77.14 percent, 81 TDs in 105 games at WR), second only to the great Don Hutson (85.34 percent, 99 TDs in 116 games)

No. 4 in TD frequency (one every 5.91 catches)

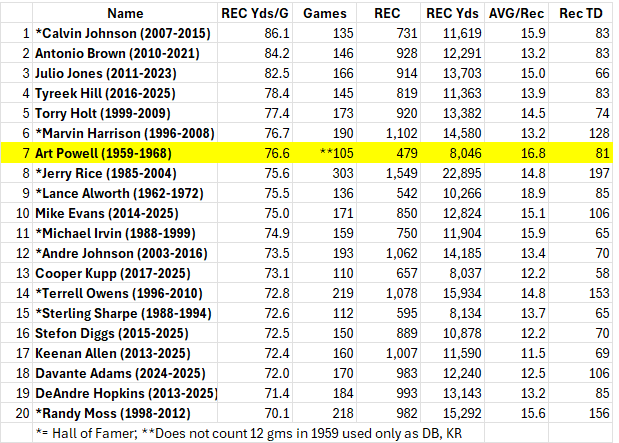

No. 7 in yards receiving per game (76.6 yards)

Let’s Drill in.

TD catches per game: No. 2 in Pro Football History

Now 57 years since playing his final pro football game in a league over 100 years old, Art Powell remains No. 2 in history for most touchdowns catches per game. In his 105 games at wide receiver, Powell’s 81 touchdown catches put him at .77 per contest.

That is second only to the legendary Don Hutson (.85) and well ahead of such honored stars as Randy Moss, Terrell Owens, Marvin Harrison, Jerry Rice … and any others one might mention.

On the top-10 list, Powell is the only eligible player not inducted.

TDs per game — No. 2

TD frequency — No. 4

Powell is fourth in pro football history in touchdown frequency, with one every 5.9 catches, behind only Don Hutson, Paul Warfield and Tommy McDonald.

Hall of Fame players indicated in gold (minimum 400 catches):

Yards receiving per game — No. 7

With more than a century of pro football data dutifully logged, Powell still stands seventh in most yards receiving per game at 76.6 yards per (counting wide receivers with at 100 games). But he was No. 1 before rule changes significantly changed the game.

The six men ahead of Powell on this list — Calvin Johnson, Antonio Brown, Marvin Harrison, DeAndre Hopkins, Torry Holt and Tyreek Hill — all played after the turn of the century, under the protection of liberalized rules favoring the health, well-being and prolific production of receivers.

Only Powell and Alworth (74.9, 1962–1972) played before the one-chuck rule in 1978, the first of several changes that limited a defender’s contact on a wide receiver. Here are the stats as of Oct. 12, 2025.

Going up!

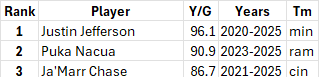

Using statistics is becoming trickier as the evolution of the game is bloating passing and receiving statistics. If we eliminate the 100-game minimum, three current stars are on pace to be at the top of the average-yards-per-game list: Justin Jefferson, Puka Nacua and Ja’Marr Chase. Here are their career numbers as of Oct. 12, 2025.

Making an impact

Statistics are great, but a Hall of Fame player must be more than numbers. He must make an impact. When he played, Powell was one of the most impactful players in pro football.

After the Philadelphia Eagles misused him only as a defensive back/returner in 1959, he had a breakout year in 1960 with the Titans, later renamed the Jets. He and Maynard each caught passes for more than 1,000 yards — a first for two teammates — and repeated the feat in 1962.

After the 1962 season, financially strapped Titans owner Harry Wismer wanted to auction Powell to the highest bidder. Powell knew he was a free agent and went home to his wife, Betty, in Toronto. Several teams were interested, and the Buffalo Bills even signed him to a contract but feared that turning that contract into the league office would cost them in compensation. There was confusion aplenty.

In December 1962, the Raiders hired 33-year-old rookie head coach Al Davis, who already knew about Powell’s ability. He saw it as an assistant coach with the San Diego Chargers while doing film cutups of the Titans.

Art Powell was the target of the first of many moves Davis would make that shocked the pro football world. His first move as head coach was to call Powell in Toronto.

“He told me he’d bought a plane ticket and for me to pick him up at the airport,” Powell said. “My wife and I took Al to dinner. We went back to our apartment, and he told me how he would give me a chance to stretch out and show what kind of receiver I could really be. Being the salesman he is, he had a signed contract with my name on it when he left.”

It was quite a sales pitch by the young coach who was taking over one of the worst teams in football after a 1-13 season in 1962. Davis arrived back in Oakland on December 31, 1962, signed contract in hand, ready to hail in a very new year, and a new era, for the heretofore woeful Raiders.

In 1963, Powell led the league with 1,304 receiving yards and 16 touchdowns as the Raiders were No. 1 with 32 touchdown passes and finished 10-4. The improvement in record marked the biggest one-season turnaround in professional sports history.

That’s impact.

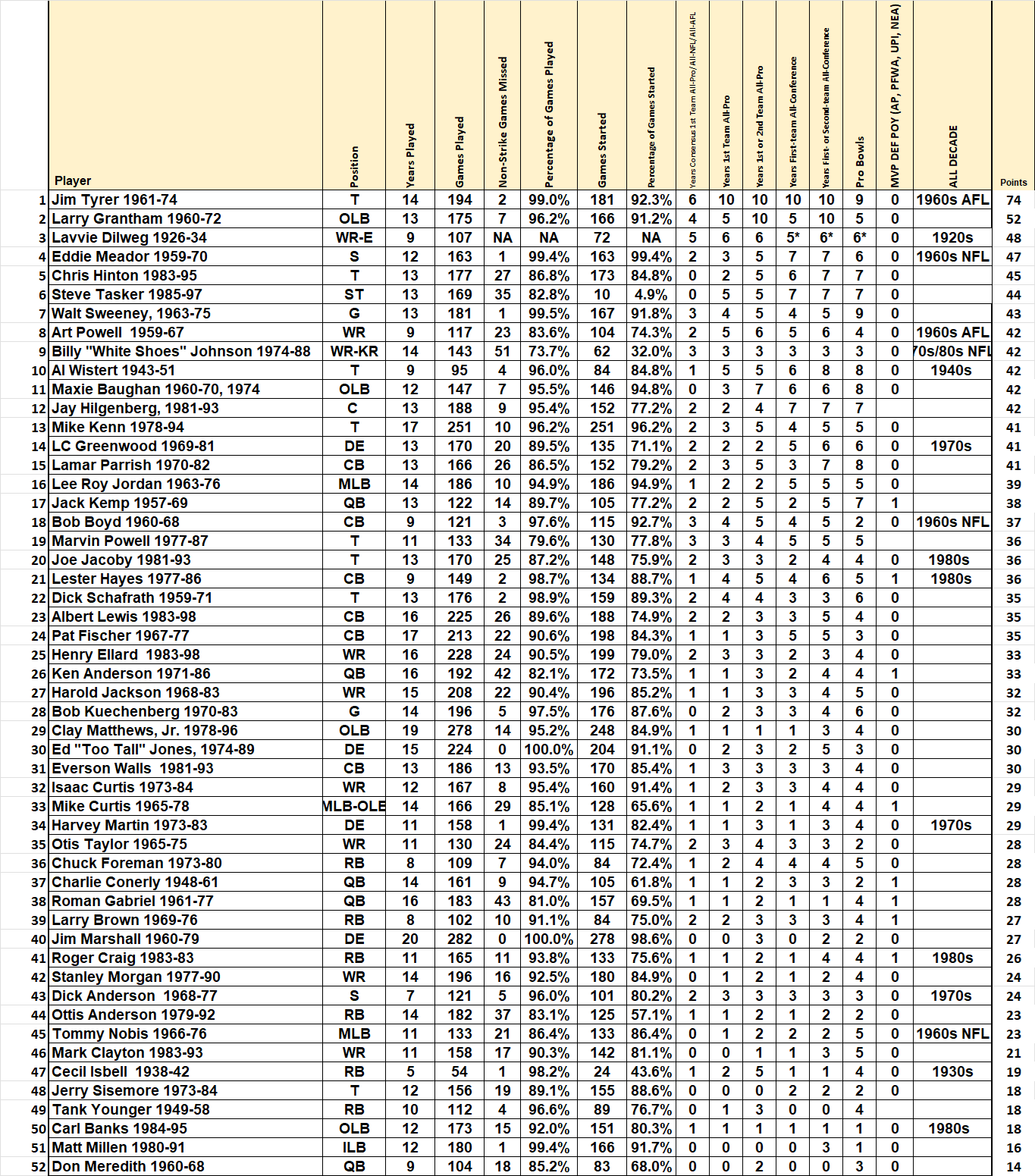

Here is a chart created by NFL historian John Turney, a member of the Seniors Blue-Ribbon Selection Committee. It attempts to create an even playing field to judge accomplishments of players over eras by assigning points to certain basics and honors that were common to all eras. This is one way to look at it, and although we like it, there are many factors that go into being Hall-of-Fame worthy.

This list of the 52 players remaining before the cut to 25 is led by former Kansas City offensive tackle Jim Tyrer, one of the most controversial candidates ever.

John Turney’s points system for all charts in this post: All-Decade = 5 points, Consensus All-Pro = 3, MVP/DPOY or All-Conference = 2 points each, Years played, Second-Team All-Pro, Second-Team All-Conference = 1 point each.

Turney is a long-time football historian and first-year member of the Seniors Blue-Ribbon Selection Committee.

🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

What a fantastic well supported piece. I knew of Powell but had never done a deep dive into his career. This would completely persuade me if I were on the committee. Thanks for sharing this.

I don't know how anyone short of a MAGA nudnik could read and digest this fantastic, and totally inclusive article on the greatness of Powell as a player, and person, and NOT vote for him!

Props to Al Davis for his genius in recognizing this great performer and utilizing him to his utmost value, as he did many others too numerous to mention. Terrific piece Frank!!! One of your very best!